Pine

October 8, 2021

Andrew Tao is a senior who is most interested in magical realism. He enjoys reading short stories and novels by authors ranging from O. Henry to Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Pine

The light was fading by the time he killed the ignition. The autumn sun hung low in the sky. Claude looked out his car window at the house, comparing the scene with the image in his head. He saw the pine tree across the lawn. It still stood a stone’s throw away from the little satellite dish they used to decorate with plastic flamingos every year for Mama’s birthday. A crown of dandelion flowers sprouted from the structure’s base, the petals now fraying into balls of white cotton, splayed outward like the collective splash of water from a fallen stone. He could see them blowing the bits of white across the lawn, him pulling grass blades together in a cross and fighting to see which would break first, her winding and unwinding the sheaths around her fingers and combing the earth for four-leafed clovers.

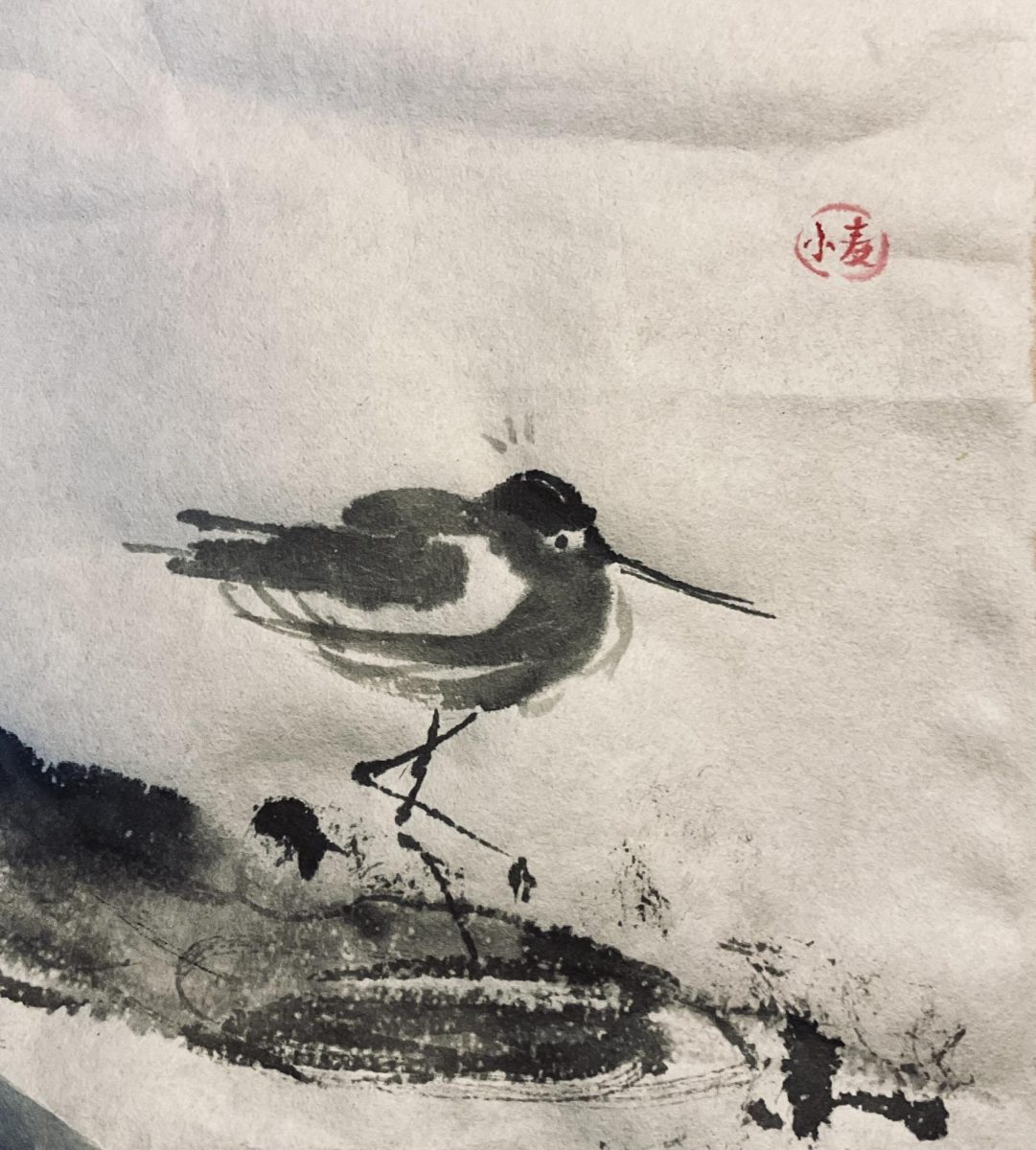

They had both called her Mama — even though she was really only Augusta’s biological mother, Claude would stay at the house so often the mailman would greet him by name and ask him how his sister was when he came down the drive Sunday mornings. With his eyes furiously scanning the body of the pine, Claude could still see lines etched into the graying bark, collectively twisting into hearts and stars and rings and birds. Looking at the attic window peeking out the roof of the house, he remembered watching for her father with her, listening to the growl of the engine grow louder and then fade and then cut out each night in the driveway. He remembered the look on her face when, one night, the money was gone and the engine never came.

They fell in love the spring the birds came early. Claude had never been comfortable with her father around the house, but with him gone, he would spend weeks on end sleeping in the low-ceilinged attic above her bedroom. Mama wouldn’t let them sleep in the same room. But at night, with the headlights of passing cars projecting the shadows of shifting vines against their curtains, they would slip notes between the cracks of the floorboards and whisper into the damp dust about the books they would read, the things they would do, the places they would see in all the days to come.

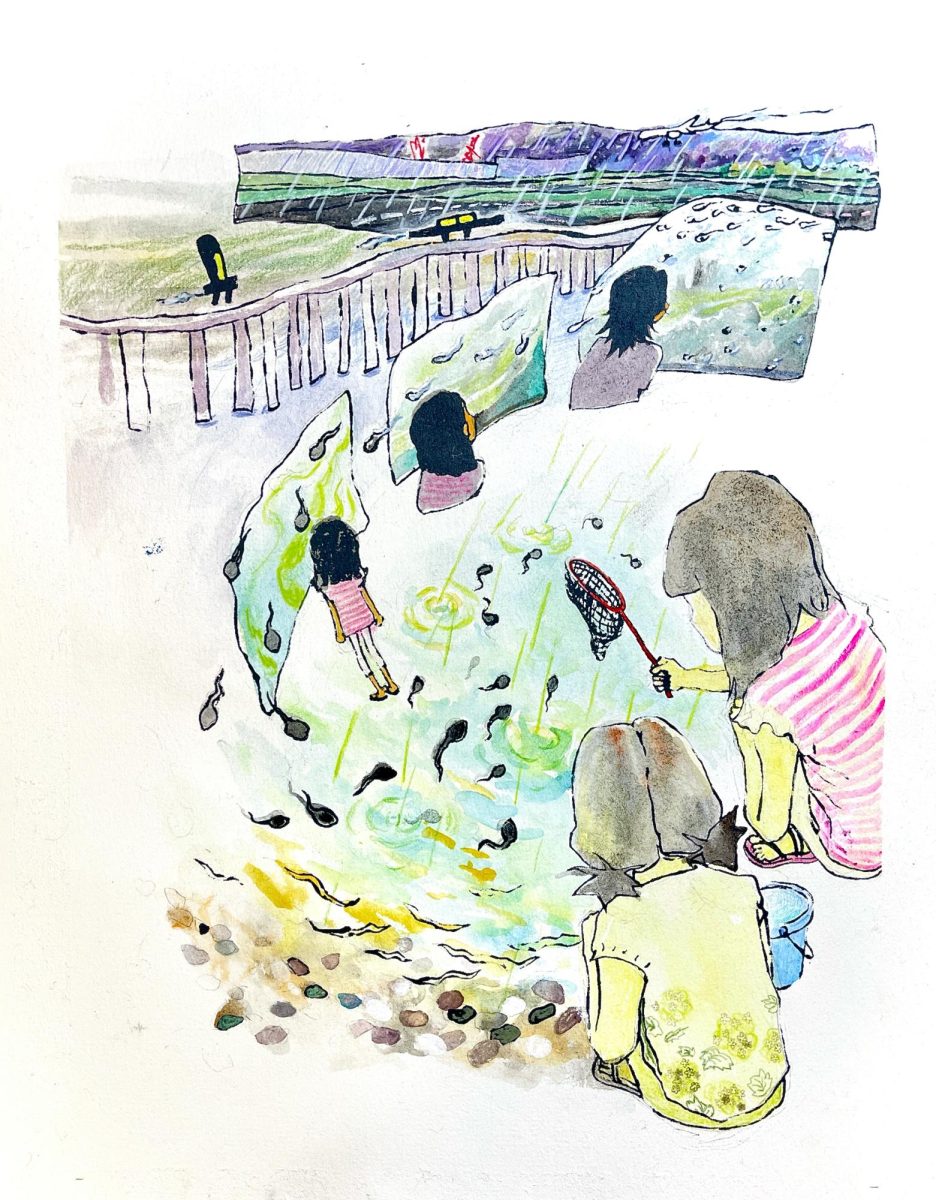

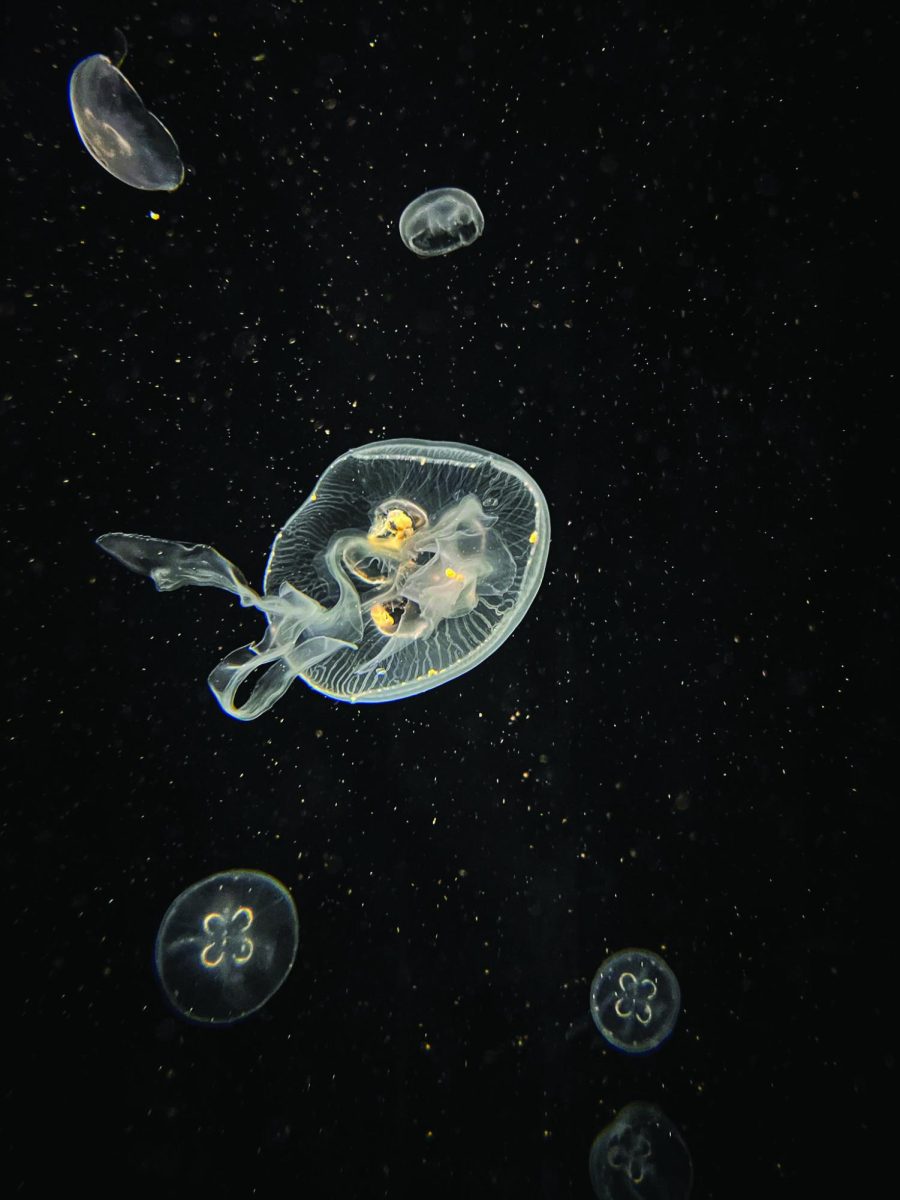

Some nights, Augusta would sneak into the attic and the room would be filled with their crying over the ending of all things real and laughing over her complaining about the sweaty boys whose pits smelled like vinegar when they tried to drape their soggy arms around her. Under the light of the moon, they would stitch little toy birds and teach them to do somersaults and to stand up to bullies and to leap and to fly. Then they would slide the curtains open, distinguish the flickering shadows, and stare at the infinity of stars in their own little square of space. In the fall they would go apple picking while the air was still ripe with promises.

It was the winter when she began seeing pink and blue. He held her in his arms and asked her what to do, then told her what to do, then screamed at her what to do. She took him to a crater in the buried cornfield, the middle of an endless sheet of paper under the multitude of stars, and asked him if they would stay burning forever. He took her hands in his and dug one knee into the ground and reached into his pocket and closed his eyes, but when he opened them again he was running far, far away. His mother had long ago stopped asking him to come home and, with his fake driver’s license in hand, he could feel the touch of freedom on his lips every day as he woke up. As he listened, the final birds of the year were passing under the sun and sounding their barbarous yawps over the rooftops of the world. The night he left, he had watched her through the floorboards and into the early hours of the morning. He had crafted the final image of her cheek into his mind, glistening with the rain that kept falling from above. He took nothing but the keys and an altoids tin filled with pine needles.

He met Mama again, six years later, down in Florida in one of the old retirement homes with the large above-ground swimming pools. He was draining it to clean the bottom of the tub of the grayed hairballs and yellowed retainers that reeked of chlorine and disinfectants. She found him with her wedding ring caught in the pool rake he was sifting through the filth and dregs of the inch or so residue of water remaining. She didn’t seem angry or disappointed when she saw him. Her face betrayed only a slight weariness as she showed Claude pictures of his son waving and smiling in a little tube swimming pool. The photograph smelled like the pine soap they would make after school together. She said he had his mother’s laugh and, after joining the middle school track team and beating all the 7th graders, his father’s propensity for running.

Claude began to linger in the playgrounds around the city, watching the cats fight around the swing sets and relishing the abuse the eight-eyed cup by the geodesic climber would hurl at him from close by. Coward. Deadbeat. Taunting. Taunting. Periodically, he would break a pine needle from the tin in two and inhale, breathing in the scent of its ghosts. He tried to imagine her face, glistening and wet, now brimming with hate. And he thought of the stars at night. Of how much longer they would continue to burn. Finally, he had lain his mattress in the trunk of the car, tossed the pile of magazines he had accumulated into a dumpster, and rested his foot back on the pedal, watching the world run in reverse of what it had done six years before.

Her house looked exactly like he had remembered it. For a moment the years stripped away and he felt the urge to sling off the straps of an imaginary backpack and break open the car door and fly up the steps to her house like a child. He put his hand on the car door handle, but when he pulled, he couldn’t twist it open. He had tried to relieve some of the tension while in his motel room earlier, lying alone on the mattress with one last magazine in hand. But nothing had come out. And as the moments ticked by, he felt he was frozen in time as well, a passive observer of the furious cars that raced by his window, leaving in their wakes torrents of leaves which swirled into tornados that killed themselves off just as soon as they were born. He felt caged and trapped and his face was molded shut and uncomfortably warm, as if it had been covered with clay and thrown in a kiln and would crack if he tried to move it or even make an expression. He was dirty and slimy and unfit and unworthy, filth beneath her feet.

After leaving the motel room, he had gone to the now fallow cornfield with a rake and a flashlight. Claude had scoured the field for a day and a night, searching through the matted stalks for the crater and the ring. Now that he was outside her house, he lifted it to the light and felt the weight of the metal in his palm. He hated the boy who had flung it into the dirt that night, who had trampled through frosted spears just to get away from those eyes that were still brimming with so much trust. The ring glinted between his fingers, and as he lifted it to his eye he noticed, through the opening of the annulus, a little toy lying in the grass. It was a stuffed animal, a wind-up baby bird. Beside the steps it stood, as if it was guarding the passage to her house. He stared at its extended wings. The wind picked up and Claude felt the inexplicable urge to reach out before it flew away.

Clutching the ring in his sweaty palm, Claude broke open the door and stepped onto the grass. He walked to the bird and knelt to pick it up. He pressed it to his lips and breathed in the smell of pine soap. And he walked the path back up to the house, ring in one hand, bird in the other, and smelling of pine all over.