Bones and Things

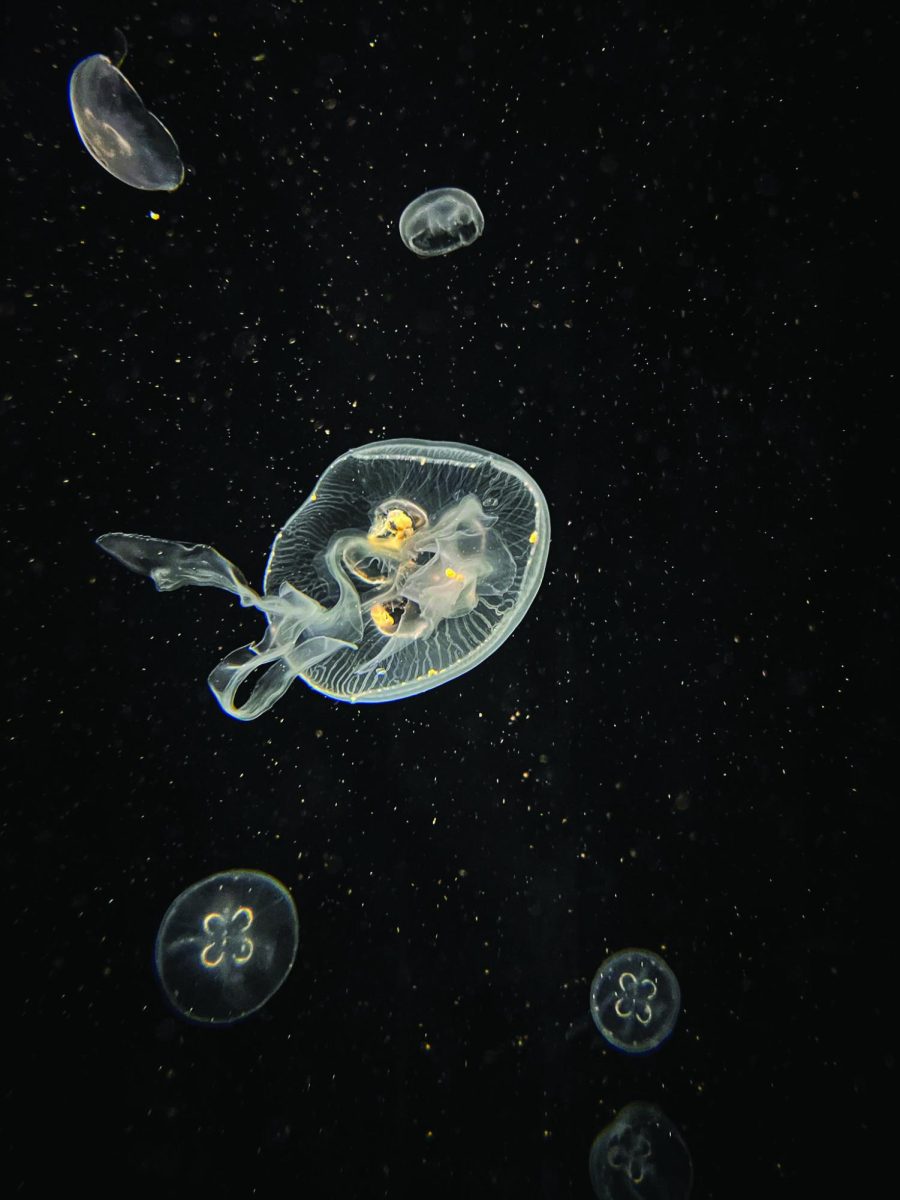

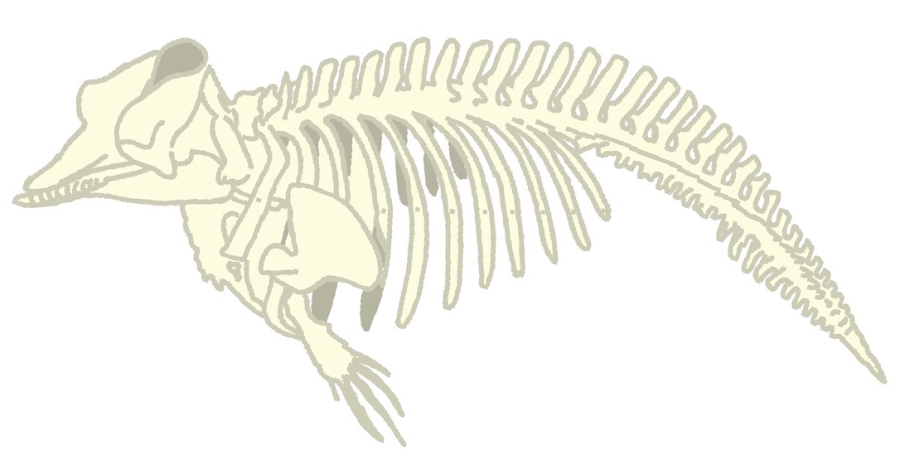

No one seemed to appreciate the curvature of the whale bones as he did. So, his class left him behind, all alone in the museum, to look at the spiny vertebrae hung from the ceiling as they seemed to drift in the drafty room as they would have years ago when the animal was still alive in the water.

Everyone thought that he was weird, including his own parents, when he came home from school one day with a crow skull, asking, “Mommy, what kind of animal is this?” The following week, it was a squirrel, then an opossum, and eventually, his bones got too big for him to take home without hearing screams.

He was never really friends with anyone, but his newfound interest in bones pushed away not only prospective friends at school but also any parents who would take pity on the boy and push their children to befriend him.

Many asked his parents if he had joined a cult. Many asked if he was worshiping the devil, but his parents just smiled and said, “Well, if he were in trouble, we’d know,” (which is so not true). “Just let the boy have some fun.”

His parents didn’t say the same thing when his sister brought home a boy. What’s the big difference between a dead bag of bones and an alive bag of bones? And why does it matter that her door needs to be kept open when he’s over? Can’t someone take stock of their collection in privacy? What if they wanted to study anatomy together?

It’s safe to say that many, including the boy himself, thought that he was a little different from everyone else. However, that’s not a proper reason to leave a classmate all alone in a museum. Well, the boy knew where to go from the aquatic exhibit; he just didn’t want to. So when the tour guide got tired of waiting for the boy to finish his quiet contemplations, they just continued leading the group elsewhere.

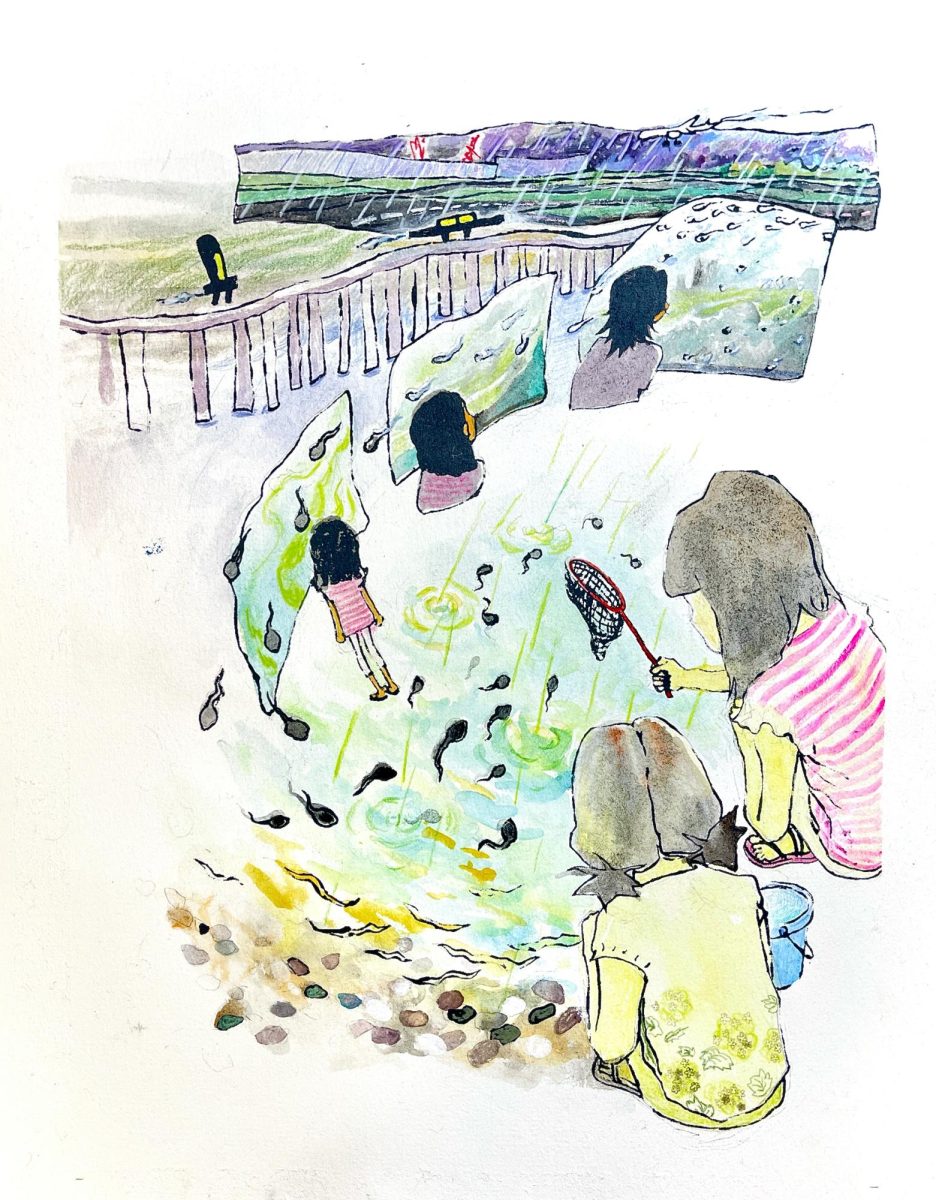

The boy was perfectly content taking his time in the aquatic room. The next room over was insects, and he had no desire to rush his art. As he did every time he went to a museum, he sketched the exhibits that he liked, whether it be a remarkably lifelike painting of a ballerina or pounds of bones held together with steel cable and invisible string. The boy liked to feel his pencil move in the soft curves of bones, see the fullness of life take shape under his hands, and gaze at his creation once he was done.

It’s not like his drawings came to life, so he always wondered why people were scared of him. They called him odd, but the only thing the boy knew that was odd was the number of vertebrae humans had.

He dreamed of studying anatomy when he grew up. He imagined that something, hidden, tucked away in the collagen structures, was what he was looking for. So, he searched. Whenever he met a new person, he tried to picture their skeleton. No skin, muscle, nerves, blood, or anything that distinguished alive from unalive. He wanted to see past all that and look at the curvature of the bone, the way it bent with stress and fractured on impact. He wanted to see his broken arm heal in real-time. Watch the break knit itself back together, more robust, more sophisticated, and ready for the next break.

There’s no real way to describe how the boy felt, staring at the whale skeleton, trying to imagine how the bones would’ve moved if it were alive, swimming along the current. He tried to picture its ribs moving with each inhale and exhale. He gazed at its fingerbones— remnants of its ancestors living on land, just like a snake’s useless legs or the human appendix and tailbone.

Even after the boy stopped sketching the whale bones, he stood there, admiring the beauty of it all. He would’ve stayed there until closing time if he could’ve, and despite thinking he should’ve, he was happy with how the sequence of events turned out.

He finally roused himself from his daydream and looked at his watch. It was time to go back home, but he feared that the buses had left without him. He sighed and accepted his fate of walking all the way. The boy peeled his eyes away from the whale bones and turned toward the museum exit.

The boy tried his best to not let any of the other exhibits distract him from his mission. It was two in the afternoon, and his big sister’s boy friend was coming over for dinner. His parents told him that it was a big deal, but he didn’t understand what all the fuss was over having a boy friend. He supposed that if he brought a friend home, his parents would be shocked, and even maybe hold a dinner in his friend’s honor.

The boy sighed wistfully as he walked home. If only people weren’t so scared of the stuff he thought was cool—all his dead things and books. He absentmindedly kicked an innocent rock on the sidewalk, jumping a bit in pain when he discovered that the rock was denser than he thought it would be. The boy pulled out his phone, checking the time. If he picked up the pace, then he could get home with time to study his new set of bones.

On his way home, the boy passed many of his usual haunts: the abandoned 7-Eleven, the Whole Foods outdoor dining area, the bowling alley where he would go to win first place against himself with the gutter boards up. He tried to keep his eyes on the sidewalk in front of him so as to not distract himself and delay his journey home any longer—he had dilly-dallied at the museum for far too long.

He saw some pretty wildflowers growing by the edge of the sidewalk and bent down to pick them up. His sister and mother would like them. He bet that his sister will press the flowers in an old book and make him a necklace out of it for his birthday, and his mother will probably put the flowers in a vase and complain when they start to wilt. His father would probably come home from work one day and look at his son’s new necklace and the flowers sitting in a vase on the dining table and laugh because it all seems very quaint to him. He’d then thank his wife for the flowers and make his children smile. Who knows, maybe the boy friend would appreciate the wildflowers as well.

The boy supposed that he had more than just bones and things waiting at home for him.

Sarina Grewal ('25) is an editor-in-chief of Ink magazine. In her two years as EIC, Sarina's favorite thing about Ink has always been the platform it provides...