M.

Asha Kulkarni is a junior who loves reading (and writing) stories that make her cry. Her favorite authors are Laurie Halse Anderson and Leigh Bardugo.

I sat on the countertop and pulled snakes out of her hair. Twisted their heads till their necks cracked, scales rippling. A sound like popping joints. Easy. She sighed as I tossed the carcasses away.

“Thanks, sis. My head feels so much lighter now. Like a cloud.”

I massaged her scalp, laughing. “How would you know what that feels like?” A shrug. She leaned back, nestling her head in my arms. “Dunno. I wonder about it sometimes. Do other kids have clouds in their hair? Or do they have animals, like me?” “Hmm. That’s a good question.”

“I wouldn’t wanna have rats. They’d probably bite worse than the snakes do. And they’re ugly.” She spread a strand of hair between her fingers. It was dark and thin, like the edge of a shadow. “But my hair’s ugly. Even without the snakes.”

“Nope.” I bopped her on the head. “Don’t say that. I’m going to make you look cute. French braids or fishtail?”

“Fishtail!”

“Okay.” I combed her hair into sections and weaved it through my fingers, humming an off-key lullaby. She sat still and quiet.

After a few minutes, I lifted my hands away. “I’m done! Ta-da!”

She pressed a hand to the back of her head. “How does it look?”

“You’re cute, trust me.”

She said nothing.

“M?” I prompted. “You okay? Want me to redo it?”

“Will you look at it from the front?” The words collapsed out of her, half-baked, squished together. I let them wobble on the floor.

“M…you know I can’t do that.”

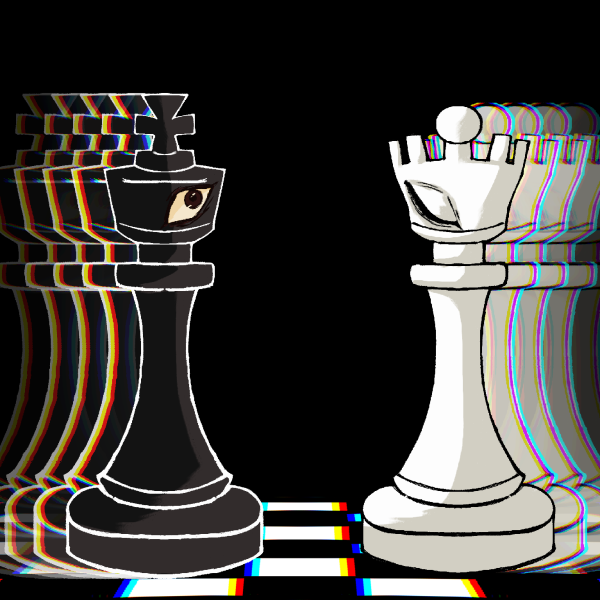

“So you don’t want to look at me.”

“I am looking at you.”

Her hunched shoulders. Her shiny hair. The three moles on the back of her neck, a few shades darker than her skin. I’d memorized how she looked; I knew her better than I knew myself.

“Sis,” she said, and I stood up and bopped her on the head again.

“Yeah?”

“How do I know you’re looking at me?”

“Well…you just know. You can feel it, can’t you? Like lasers.”

“Lasers.” I could hear her frown.

“Little red lines. Pew pew! Cool, right?”

She shook her head. “I wouldn’t wanna have lasers for eyes. Cause then I’d kill you if I looked at you.”

I stared at the snake corpse next to my foot, at its wide eyes and limp body. Death had done that; Death had skittered across its scales and stiffened its tail so it lay flat on the floor. It had happened so quickly.

“You’re probably right,” I said. “Lasers are bad. Just know that I’m looking at you.” “Okay.” M picked at her nails.

God, I was a terrible sister.

I picked the snakes off the floor and shoved them into a black garbage bag. Hoisting it over my shoulder, I walked to the door.

I placed my hand on the knob. “Are you listening?”

“Yeah.”

The wood stared back at me.

“Remember the rules. Stay put, stay low, and whatever you do, don’t…”

“Look out the window. I know.”

It felt like a snake had wrapped itself around my stomach. I didn’t want to leave her there.

“I’ll be back in two minutes, okay, M?”

“Okay.”

I opened the door.

It was dark outside. Our driveway stretched several yards away from the house, illuminated only by patchy moonlight and the tiny yellow bursts of streetlamps. Three trash cans crowded together at the end of the driveway; their black silhouettes looked like boulders.

I made my way over to them, the plastic of the garbage bag sweaty in my hand. Dead snakes were heavy. It felt like I was carrying stones.

I lifted the lid of the first trashcan and dumped the bag inside. Thunk. The garbage truck would pick it up tomorrow morning before the corpses started to reek and draw complaints from our neighbors.

Wiping my hands on my jeans, I walked back up the driveway.

The windows of the house were dark, swathed in tape that I’d layered on years ago. It blocked all light from entering or leaving. You couldn’t see inside.

But the moon must have hated me, because its white light danced across the windowpanes and turned them into mirrors. It would have been poetic if I was someone else. Don’t look. Don’t look.

Too late: I saw the green eyes and the green hooked nose, the halo of reptile bodies that wouldn’t stop moving, sprouting from my scalp. The snakes that, if they were killed or yanked out, would take me with them, that would suffocate if I covered them because I was the loser of the genetic lottery, the freakish child of parents with heads of human hair. M was halfway normal, but I was different. I was worse.

I shook my head and turned away from my reflection, unsure whether to be thankful that I could see myself and still retain my skin.

I reached the door and paused with my fingers on the knob.

“I’m going in,” I called out. “Stay where you are. Don’t come over here.” Silence. The glass warmed in my hand.

“M?” My voice jumped an octave. “M, are you there?”

There was no response. My snakes hissed and coiled tighter, responding to my mood. A shed skin plopped onto the welcome mat. I kicked it away and pounded on the door. “M! Where are you?”

Nothing. Had she hurt herself? Did a snake bite her? What if she was lying on the floor, bleeding out, and I was too much of a coward to help?

But what if I ruined everything?

“Help!” The sound came from the other side of the door, my sister’s voice as loud as I’d ever heard it.

I didn’t think; I just rushed inside. “M, what happened?”

She barrelled towards me from the other end of the living room. A blur, too fast for me to see. A shooting star.

“Will you fix my hair? My braids came out and now it’s all tangled, and I don’t know what to do and I need it to look pretty, because maybe then you’ll look at me. And maybe Mom and Dad will come back…”

I stumbled, my breath evaporating. “Don’t come closer! Stay back! It’s not your fault, but you need to stay back!”

“I don’t have lasers for eyes! Why won’t you look at me?”

“M, no!”

She stepped closer, sobbing, and I saw that her eyes were moons, the black sky almost eclipsing the white. Dilating.

(She was looking at me. I’d never seen her face before).

It happened in an instant.

I blinked, and she didn’t. I moved my arm, and she didn’t. I cried out and felt my chest shudder, but she stayed still: eyes open, hands stretched in front of her, hair still spilling out of her braids.

Gray color crept up her skin, covering her completely. Her moles, her lips, the color of her eyes: the gray coat drowned it out. A snake would never sprout from her head again. Snakes liked the warmth, and M: she was stone cold.

7 years old, forever.

How would I haul her into the attic? It would be harder this time; M wouldn’t be there to hold the ladder, laughing at the terrified eyes of the statues and believing they were off-brand art, not the people who’d given life to us.

I’d manage it, somehow. I’d shut her inside and they’d all be a happy family. Snakeskins rained down on the floor.

I brushed my finger against M’s cheekbone and heard her voice in my head. Thanks, sis. Why had I even tried? It was doomed from the start. My parents… They’d named the wrong one of us Medusa.