“Let’s start class by going around the room and saying what we did this summer.”

I almost leave then and there. I’ve had enough of people asking where I was last summer, let alone the past two years. I tell them I was living with my sick grandma or me and my family moved to Tokyo for dad’s work. I’ve always impressed myself with how quickly I can come up with a lie. You have to give me credit for my creativity.

“Nothing much, I went to sleepaway camp.”

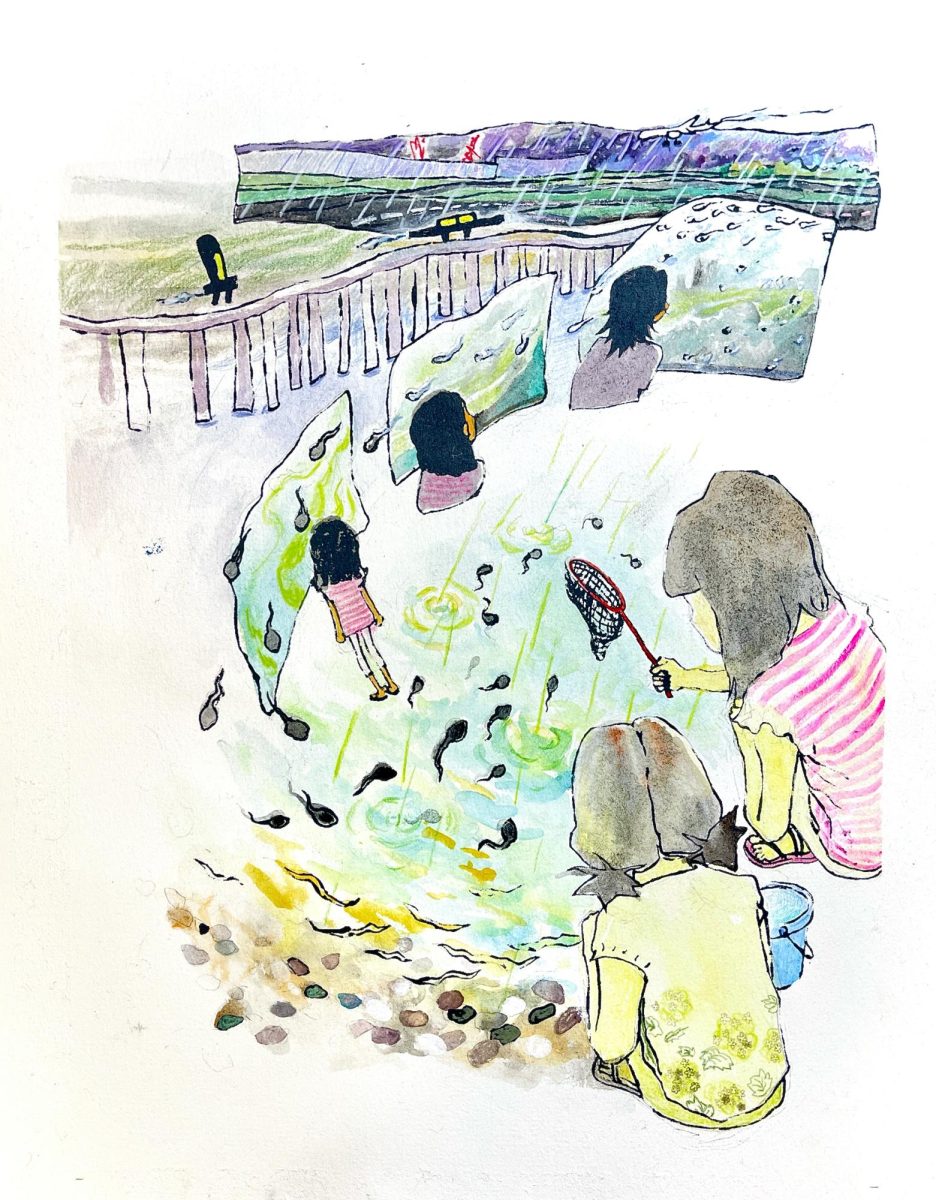

I’m relieved when my teacher doesn’t make me elaborate. I doubt she heard me. She probably should have retired a decade ago when she could still hear and see more than two feet in front of her. I’m not lying– wilderness therapy is basically summer camp, but for those of us who decided substances were our best friends. We made friendship bracelets and went on hikes to “help us realize the value of our lives” and “send us on the right path”, just not necessarily because we thought it would lead to some summer fun. The kid in front of me makes a 180 in his desk.

“Hey, man, how have you been? Do you remember that project we did together in 8th grade? It’s been a while.”

If I remember correctly, Thomas Bicudo spilled a whole glass of milk on our civil rights poster the day before we presented it. People laughed when they saw our smudged poster, and I had to explain to everyone that it wasn’t me who was incompetent.

“Yeah I’ve been good, I was staying with my uncle in California.”

I wonder how long it will take for people to realize I’m lying. It’s a little bet I’m making with myself. I’m not a serial liar, I just think it’s nobody’s business.

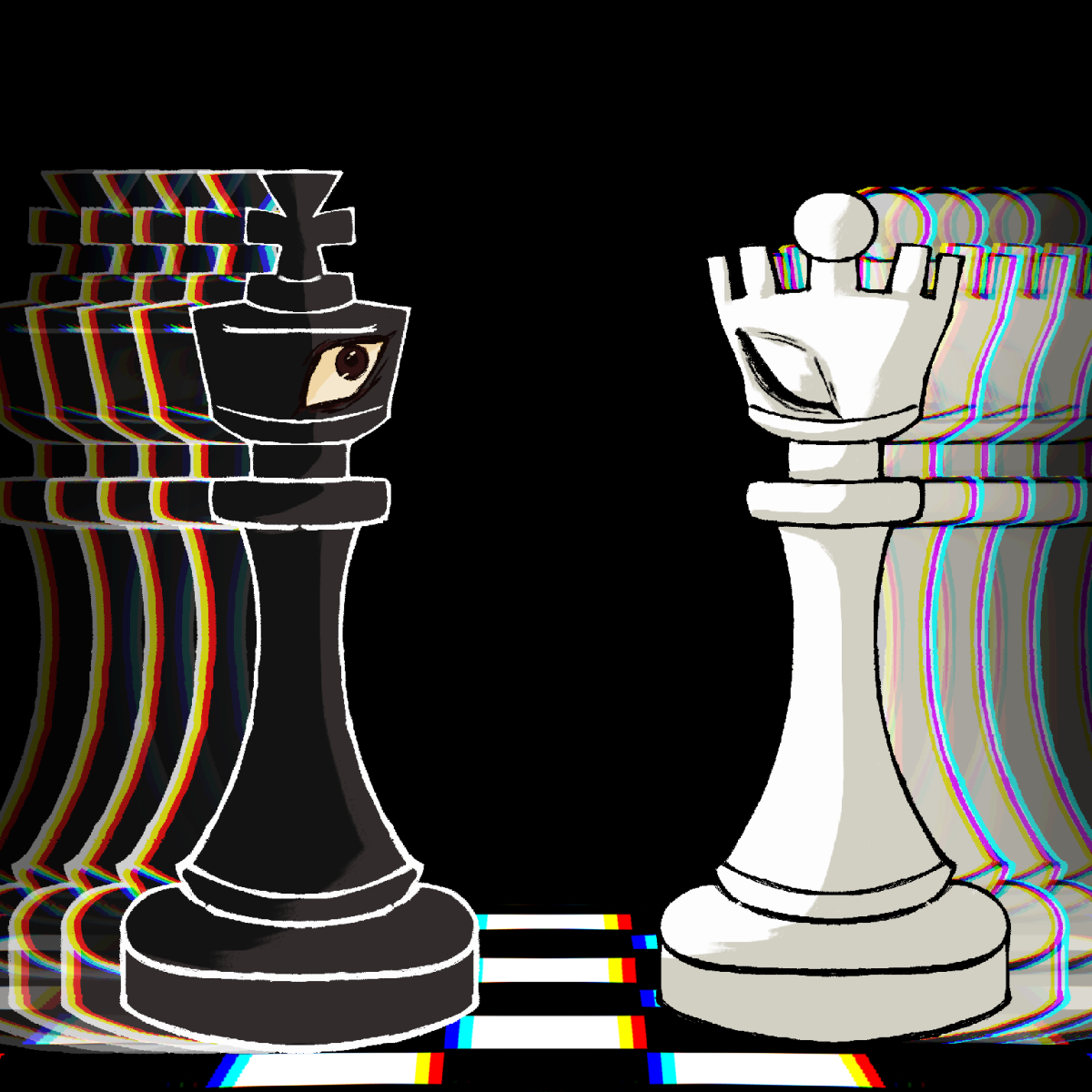

What’s worse than the people who quiz me about where I’ve been all this time are the ones who won’t even look at me. Even those whom I used to call my best friends don’t acknowledge my existence. I passed by Theo Carter in the hallway after 1st period. He’s gotten tall, almost as tall as me. He’s built like a football player, broad-shouldered and built. The kid whose house I would go to every day after school from ages eight to twelve, I am now trying to avoid eye contact with. I even told him about my parent’s divorce. It’s the same face, even under the four o’clock shadow, but a completely different person. I wonder if I look as different to him as he does to me.

Today I’m going to my first ever therapist meeting after school. My dad never encouraged me to talk about my feelings, he called therapists and counselors frauds on multiple occasions, and he was a firm believer in the rule that boys shouldn’t cry. I think it was his new girlfriend’s doing, a 30-year-old Vietnamese woman whom he met on a cruise a year ago. I met Kim a month ago and she’s already roleplaying as my mother. She loves to insert herself into my life and give me advice on how to “manifest a better future.” She and my dad meditate outside every morning. He’s a different man than he was when he was married to my mom, and sometimes I wonder who I would be if this version of him raised me: with love and patience instead of anger.

The therapist’s office is cold, blasting its AC despite the Michigan weather that never seems to go above 80 degrees. I walk up to the lady at the front desk, who doesn’t look up from her furious typing for at least five minutes.

“Hi hon, give me a second.”

Another few minutes pass by. I wonder what she’s writing. Maybe it’s a novel on how to be the world’s worst receptionist. She finally looks up and peers at me through her glasses.

“Well, I didn’t expect such a handsome young man. Do you have an appointment?”

I laugh just enough to pass for a thank you.

“Yeah, for 3:30.”

“Ok. Anthony? Take a seat.”

I nod my head and walk over to an ugly blue chair by a window and a stack of magazines. I’ve gotten used to middle-aged women calling me handsome – I almost expect it now. The men usually call me pretty boy and give me a pat on the back, afraid that any hint of a real compliment will make people think they’re gay. The best part about being attractive is that I don’t always have to put on my A-game personality for people to think of me as charming and likable.

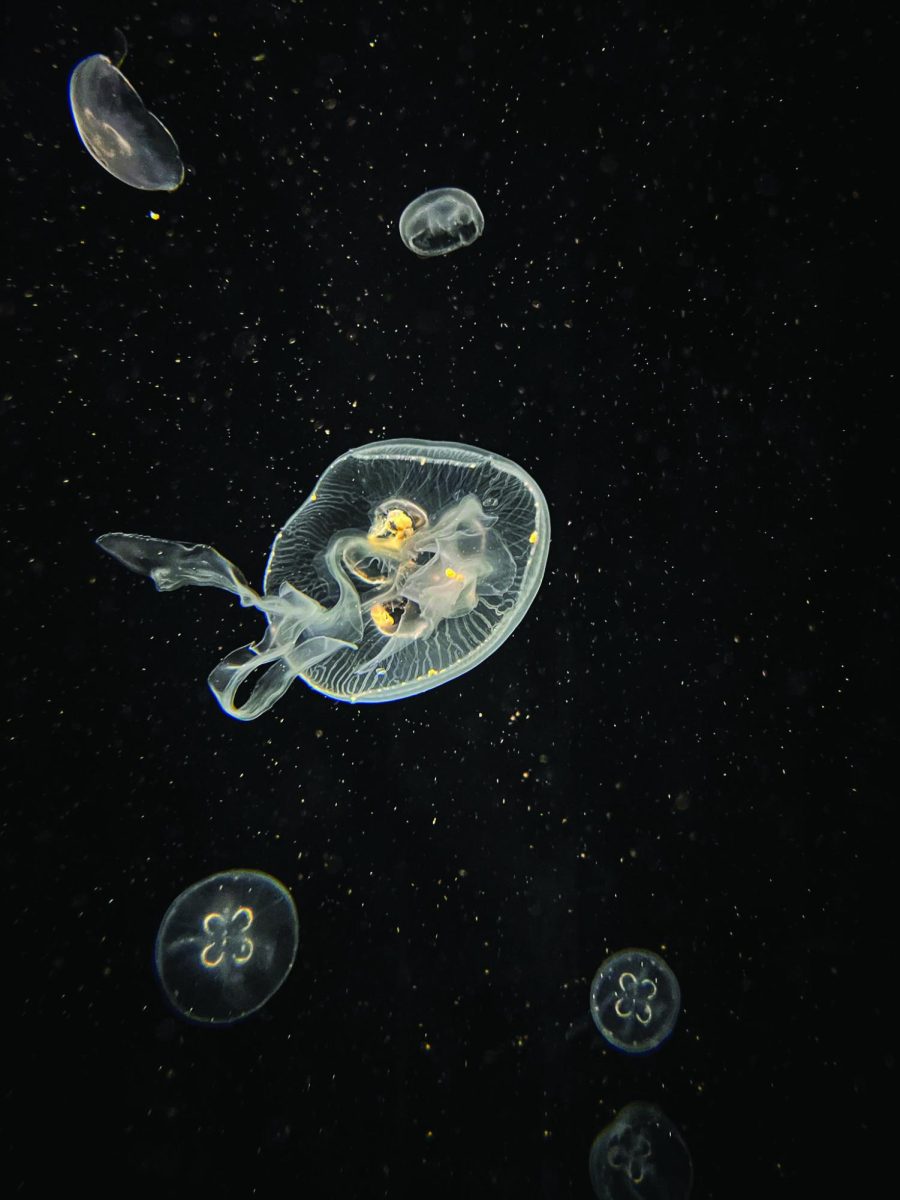

The office is empty, and I start to wonder what kinds of people this place has seen, how many people have sat in this chair and looked out this stained window. There’s a tree a few feet away from me that is identical to the one outside my old house, except duller, and the leaves fill it more sparsely. After a couple of minutes, a tall bald man in a polo and blue jeans comes out with a clipboard.

“Anthony?” He says, looking at me.

I try to smile and walk ahead of him into his office.

“Your mom called and said you have been struggling lately, and you just got out of rehabilitation.”

“My mom?”

“Kim is your mother, correct?”

“Oh, no. That’s my dad’s girlfriend.”

“Well, I’m glad to see someone is looking out for you.”

I give an unconvincing smile and feel a new pit form in my stomach as I realize it’s not even my own parents trying to help me. They never knew how.

“So anyway, I understand you used to live in Chicago with your brother and mom until you went to treatment. How is the adjustment to living with your dad now? Or even getting out of rehab?”

He looks bored and tired. Like asking me a simple question just took all the life out of him. At least we both don’t want to be here.

“It’s been fine. My dad is trying to get me to do construction work with him.”

I smile and try to keep it lighthearted, but he looks at me long enough to let me know he can see through that. I start playing with a rubber ball he put out on the table until I realize how much of a child I must look like and immediately put it back down.

“What were things like back at your mom’s house?”

Blood rushes to my face. I think back to the end of 9th grade when I was still with her and Luca. Tears come to my eyes and I can’t speak. When I think of her all I can see is the pain in her face when she found my stash. She held it up to me and asked me why, why I would do this to her. It’s the reason I asked to stay with my dad. I didn’t ruin his life. I clear my throat but my words still come out shaky.

“Fine.”

My pulse beats in my head, and before I know it, I’m halfway out the door. I keep my head down and make it to the alleyway by the building before the tears finally slip out. I walk all the way home thinking of nothing but the interaction I just had and praying no one I know sees me and my puffy eyes. When I get home, Kim’s in the kitchen.

“You’re home so soon?”

“Yeah, it was a short session, just getting to know each other.”

I walk past her. I just need to make it to my room and then I’ll be okay. I lay in bed and finally let myself go. My crying starts out soft and then the heavier wails begin. I bury my face into my pillow, deep enough so no one hears. The crying doesn’t seem to make the piercing pain in my heart go away. Why did he have to ask me about my mom?

Hours pass by and my room is bright with lights that I don’t have the energy to turn off. I hear the door open and I close my eyes as fast as I can, pretending to be asleep. I assume it’s Kim, coming to bombard me with more questions, but I hear my dad’s voice.

“Hey kid, how’s it goin’?”

His tone is something I’ve never heard from him before: soft and compassionate. I open my eyes and lift up my head to see a bowl of soup in his hand. He puts it on my nightstand.

“Kim made you some food.”

I sit up and avoid his eyes.

“Thanks.”

“Dr. Baker called me. He said you left early after he mentioned your mother. He wants to up your meetings to three times a week.”

I feel a wave of anger and look up at his face to argue until I see his eyes are glassy and his eyebrows are creased with worry. My mind goes back to the time when I was ten and I fell off my bike outside of our house back in Chicago. My dad was the only one home and came running out when he heard me screaming. My arm was twisted unnaturally and I was desperately crying. He looked at me with the same expression he does now.

For a second, I saw myself how he must see me. His firstborn son. His little boy he used to go fishing with and read to sleep every night. His baby, who would run into his arms every day after preschool, who he bragged to his friends about when he was the best on the baseball team, who he went to Cubs games with, who he called his “little buddy,” who he helped with homework and taught how to shave, and who he had to take to rehab after finding him on the floor of his room with throw-up staining his carpet.

“Please, Anthony, please try.”

His voice is almost a whisper.

“Okay.”